When Georgia Square Mall opened in the early 1980s, downtown businesses headed for greener pastures, or at least what used to be pastures. Drawn by cheap rents, artists and musicians moved in, turning downtown into the quirky, dynamic place we know and love today.

Auto-centric strip malls were the future then, and downtown main streets were the past. Ironically, now it’s the big boxes and shopping centers with acres of parking that are in danger, and downtown is in some ways a victim of its own success.

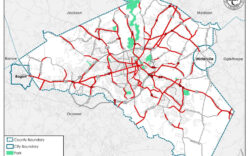

Let’s be real: Atlanta Highway kind of sucks. It’s the antithesis of what we think of as Athens—sprawling and full of chain businesses. It might as well be Snellville. But its franchise restaurants and big boxes employ thousands of people and bring in millions of dollars in tax revenue to the city. We can’t afford to let it die.

With a new outdoor mall in Oconee County threatening to pull in retailers from Atlanta Highway, Commissioner Mike Hamby put together a committee last year to find ways to revitalize the corridor. That committee is paying the Urban Land Institute $15,000 to brainstorm ways to fix the ailing corridor. The institute brought 14 experts to Athens Thursday and Friday to take a look at it for themselves.

They advised ACC officials to come up with a strategy, build relationships with property owners, relax development standards, provide tax incentives for job creation and improve signage. It all sounded pretty rote, until Ryan Gravel spoke up.

Gravel is an urban designer who came up with the idea for the Atlanta BeltLine, the transit and pedestrian loop that promises to spur sustainable development in intown neighborhoods.

“Oconee County is pursuing an outdated strategy,” he said. “In my opinion, it’s a mistake to do what they’re doing.”

The creative types who saved downtowns like Athens’ are now being pushed out as those downtowns gentrify and become more mainstream, Gravel said. At the same time, many cities like Athens are also having trouble with vacant retail space in their suburban corridors. Why can’t creative people do there what they did downtown?

“These can be kind of low-cost areas where people can get creative and do something interesting,” he said. “But that might require lowering your standards” to give them the freedom to do it.

He cited the example of Buford Highway, another aging commercial corridor that found new life as a regional destination for ethnic food. Maybe something similar could happen on Atlanta Highway with music.

What if we convinced Georgia Square Mall to tear down its outbuildings and some of its parking and replace them with greenspace, gathering places like coffee shops and a stage where families could see concerts? What if we encouraged developers to turn the shells of big boxes into lofts, artists’ studios, offices and band rehearsal spaces, the way we do with abandoned industrial areas like the Chase Street warehouses? What if we created a semi-walkable environment and connected the strip malls along the highway so shoppers didn’t have to get back in their cars, turn left across four lanes of traffic and drive a quarter of a mile to get from Toys ‘R’ Us to the mall?

“You can’t compete with the suburbs,” Atlanta transportation planner Heather Alhadeff said. “You have to recognize your uniqueness. You have to grab it. You have to celebrate it.”

Southern Mill: Speaking of redevelopment, a Watkinsville-based developer has submitted plans to turn a century-old Boulevard mill into lofts.

Millworks Holdings, a Watkinsville-based company, intends to renovate four vacant mill and warehouse buildings north of Oneta Street and west of Chase Street into what was known in a previous incarnation as Southern Mill Lofts. (An unnamed company representative said in an email that the project is now called Millworks.)

Although it’s an attractive 18-acre site just blocks from the Boulevard neighborhood and the Chase Street warehouses—a similar and successful adaptive reuse project— the property has sat vacant for years.

The Athens-Clarke Heritage Foundation owns an easement on the buildings’ facades, and the developer is applying for state and federal tax credits that will require preserving the interiors as well, ACHF Executive Director Amy Kissane said. The State Office of Historic Preservation and National Park Service will have to sign off on the plans.

“With the facade easements, they are required to preserve the exterior of the building,” Kissane said. “Going for those rehabilitation tax credits means they will be held to the highest standards in our codes, which is great news.”

The Southern Manufacturing Co. built the mill in 1900 to process cotton that was shipped along the railroad running adjacent to the property. The Wilkins family bought it in 1953 and started manufacturing overalls, slacks and blue jeans and storing dog food there. But like most of Northeast Georgia’s mills, it closed and lay dormant before Atlanta-based Aderhold Properties bought it in 2000. The Athens-Clarke Commission approved Aderhold’s plans that year, but they never came to fruition.

In an effort to generate interest in the property, the Athens-Clarke Heritage Foundation and the University of Georgia College of Environment and Design held a charette and symposium last year to discuss what could be done with it. Ideas participants came up with included an arts community with affordable housing and studio space, an assisted living center with live/work space for caretakers and an incubator for light industries.

Millworks Holdings isn’t using any of those ideas, though. Instead, it’s using the plans already approved by the commission 13 years ago, except it’s not proposing any new construction, ACC planner Gavin Hassemer said. The complex will now include 181 units with a total of 262 bedrooms, as well as a parking lot.

“It will not be student housing,” Kissane said. “They’re doing more creative residential.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.